You don’t hear this one as much, but the concept infiltrates and sabotages much of our evolutionary thinking, limiting our understanding of nature, and, worse, leading us down that dangerous path to apathy, hate, and violence.

Here's the trouble with forwards and evolution.

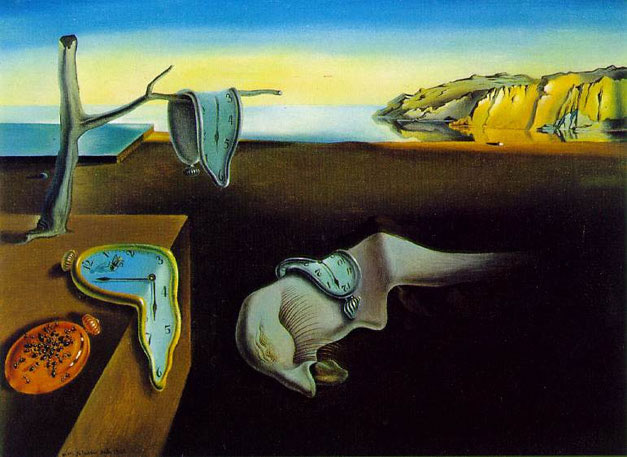

Time goes forwards. It's singular and linear. You might call it an arrow (like Carroll) or persistent (like Dali), but you wouldn’t call it progressing or progressive. That is, a minute now isn’t any better than a minute 30 minutes ago. A minute now isn't an improvement over a minute 30 billion minutes ago.

This is a very simple, value- and progress-free understanding of forwards that isn't transferred onto biological evolution.

Instead, with biology we equate forwards, or the passage of time, with progress but this is a biased view of nature.

Time goes forwards. Complexity requires time. Okay.

Yet, onward-and-upward-ness is our invention. It's a cultural notion, that we can't help but project onto nature. And if you see traits changing through time as each phase being better than the next, as being a part of some cosmic progress, then you’re falling into a dangerous trap.

While you're trapped by forwards-thinking, you might assume that:

(a) prior states of traits were worse than present ones

(b) losing a trait is bad

(c) traits that are not as complex/large/fast/furry/slimy/etc as in prior states are somehow lacking

(d) present traits that resemble earlier versions are somehow lacking, in other words, "primitive" traits are valued less than derived ones.

The last one can rear its ugly head when we naively or carelessly use our completely acceptable evolutionary jargon to describe human variation: Some people are derived at trait X, while others are "primitive."

(Can you call it an f-word if it starts with a p? Because "primitive" might need to get censored from evolution-speak too.)

While you're trapped by forwards-thinking, you might refer to early hominids as “proto-humans” implying they’re an imperfect draft or prototype and that they're not quite perfect or human. If this is true, then we’re proto-Pauls.

Try this. Get in your DeLorean, and set the dashboard to 50 million years ago. Make sure your flux capacitor is engaged and then drive 88 mph down your street and... Voila! You're back in time. Now, are all the animals drooling all over themselves, barely able to eat, walk, or do whatever it is that they do?

Of course not. They’re getting along just fine.

Evidence? Look around you in the year 2011. Nothing would be hunky dory now if nothing was hunky dory in the past.

Yet, 50 million years ago is full of half-baked, inadequate organisms like “proto-whales” and “proto-lemurs” and “proto-bears.” That’s because we have few ways to describe them in such a way that links them to their present-day relatives. They're ancestors or relatives to present day species and we can make those links thanks to some traits they share in their anatomy. But they're not prototypes of anything. They're not anticipating anything. They're not becoming anything. They're just anything--like you and me today are anything.

While you're trapped by forwards-thinking, you might even use the non-term “devolution” to describe the loss of a trait, or the decay of a trait or the decline of a trait. But that’s just evolution. Forwards/backwards, new versions/reversions, gains/losses... All that's just regular old evolution with our biased, value-laden vocabulary (and our aversion to reversion) draped over it. Thinking there's a backwards in nature is just backwards thinking.

We all fall into the forwards-thinking trap. We all have trouble escaping our linear, progressive, goal-oriented thinking. It’s difficult to step out of our present perspective and our culture while we absorb the evidence for evolution. Of course, it's hard... We're complex!

But there are lots of organisms that we wouldn't call complex that are just fine at doing their simple things. Furthermore, there are lots of traits within complex organisms that haven’t changed over millions of years because they’re fine just the way they are. DNA is just one example. Not only have there been myriad additions to organismal complexity during the span of Life on Earth, there have also been myriad losses of functioning

tr

aits as well.

aits as well.That certainly doesn’t sound like nature is progressing towards a goal or even just towards ever-increasing complexity for complexity’s sake.

Just because we consciously create increasingly complex technology ... just because we marvel at complex systems... just because we appreciate and even strive for complexity…just because we celebrate forwards-thinking... and just because we teach and reinforce goal-oriented behavior... that doesn’t have any bearing on what matters in nature.

Nature cannot strive for, marvel at, celebrate or appreciate, remember?

In nature, there's no forwards or backwards. Nature just is. What works works. What doesn’t doesn’t.

Some of it’s beautiful and some of it’s brutal, but nature has no idea.

Beautiful and brutal and forwards-thinking are ours.

Thanks to nature.