The media frenzy last week over the new Australopithecus sediba papers coincided with all of my new

faculty events on campus. Whenever I was asked to introduce myself and to

describe what I teach and study, every response I heard had to do with the

recent reports of fossil hominin discoveries from Malapa, South Africa.

"I just read about some fossils on msNBC. So that's what

you're into?" … "How about those new finds! Wow!"

And although anything as equally well-preserved as the sediba stuff, but from 18 million years

earlier (like, say, new fossil primates from Rusinga Island) would be greeted

with relatively weak popping of eyeballs and with barely perceptible gaping of

jaws, I'm pleased to be so quickly matched to my field of study. I'm delighted

that paleoanthropology's so prominent in the media. Who doesn't want their

passion to be bathed in limelight? (Besides independent music fans.)

But why does paleoanthropology seem to garner and even hog so much attention? This is a sometimes perplexing pattern in the science news and here's a little back and forth between Ken and I inspired by this question.

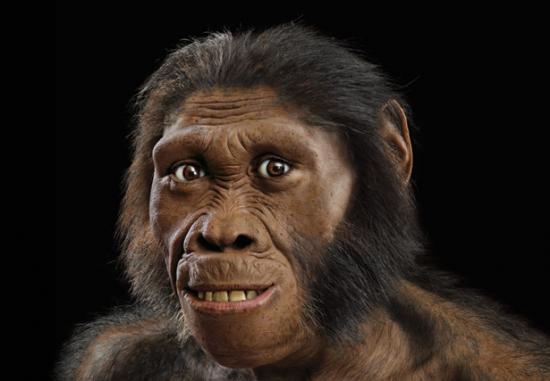

Ken: What, if anything, is this [the

new A. sediba finds and analyses]

really saying that we didn't already basically know?

Holly: We don’t know much about the time frame between

2.5 – 1.5 million years ago and this is when a lot of changes take place that

trend toward human-ness and away from ape-ness. The Malapa fossils (A. sediba)

preserve both cranial and postcranial bits of single individuals, so

proportions of brain size, body size, limbs, teeth, etc can be studied which,

again, is a rare opportunity for the hominin fossil record for this time period

which is comprised mainly of cranial and dental remains that even with a

well-preserved braincase for estimating brain size, don’t come with associated

postcranial or skeletal bits for putting that brain size in context. The Malapa

homs had small early hominin (read: ape) sized brains at a time in hominin

history when we hypothesize and even expect hominins to have relatively larger

brains. Many would also expect them to have larger brains given the modern

aspects of their hands and pelvis. Furthermore, the skeleton—from the hand to

the pelvis to the foot—shows a new mosaic of human-like, biped-like, homo-like,

australopith-like, and apelike traits. Lucy (A. afarensis) is famous for

showing a mosaic of these things but the Malapa finds show a different mix. These

finds are a window into the process of evolution, to the order of when traits

like we have appeared in the past. And even if it’s a tiny little momentary portal,

it’s still a peek!

Holly: We don’t know much about the time frame between

2.5 – 1.5 million years ago and this is when a lot of changes take place that

trend toward human-ness and away from ape-ness. The Malapa fossils (A. sediba)

preserve both cranial and postcranial bits of single individuals, so

proportions of brain size, body size, limbs, teeth, etc can be studied which,

again, is a rare opportunity for the hominin fossil record for this time period

which is comprised mainly of cranial and dental remains that even with a

well-preserved braincase for estimating brain size, don’t come with associated

postcranial or skeletal bits for putting that brain size in context. The Malapa

homs had small early hominin (read: ape) sized brains at a time in hominin

history when we hypothesize and even expect hominins to have relatively larger

brains. Many would also expect them to have larger brains given the modern

aspects of their hands and pelvis. Furthermore, the skeleton—from the hand to

the pelvis to the foot—shows a new mosaic of human-like, biped-like, homo-like,

australopith-like, and apelike traits. Lucy (A. afarensis) is famous for

showing a mosaic of these things but the Malapa finds show a different mix. These

finds are a window into the process of evolution, to the order of when traits

like we have appeared in the past. And even if it’s a tiny little momentary portal,

it’s still a peek!Ken: Why is it that a single new find can 'revolutionize' our understanding of 'what makes us human' and all that BS? If we are so vulnerable to a single new find, then why do we insist on making such bold claims about what we currently have?

Holly: I think

that some of it has to do with the colorful personalities of the people who are

drawn to paleoanthropology—the scientists, writers, reporters, critics, fans

etc. If you care so much about your fossil relatives, that’s pretty

narcissistic isn’t it? I’m not sure new finds revolutionize anybody’s understanding

of “what makes them human” unless they’re

new to paleoanthropology. First-timers to the fossil evidence are probably

blown away and their world-views are changed, but long-time fans would probably

describe their new perspective as hypothesis creation or story change. And yes,

new finds do re-write the story of human evolution if your story includes

details beyond “We share a common ancestor with chimpanzees about 6 million

years ago and since then bipedalism and big brains evolved.” But even that

story could be re-written if we find fossil evidence that bipedalism preceded

the LCA (last common ancestor) with chimpanzees.

Why do we “make

such bold claims about what we currently have?” I don’t think paleoanthropology

holds the monopoly on this behavior. As we discuss on the MT quite a bit, this

is part of the game of science and academia, of getting tenure and promotion,

of getting grant money.

I also think

that paleoanthropologists are simply excited about their finds and can’t help

but share that with the rest of us. If that excitement draws science-deniers

closer to the light, then that’s a huge bonus.

I think there are only so many ways to make sausage. I'm pretty sure that's not the right idiom, but I'm trying to say

that there are only so many ways to garner interest for news reports on new

fossil hominins... so they all start to sound the same. Unless you read further

and learn the ins and outs of paleoanthropology, then each new fossil is

interesting in that informed context, from that informed perspective. If you do

a search, all the phrases are the same for fossil news but if you search for

reports on raging fires you find just as much repetition/unoriginality. There

are only so many words and phrases at our disposal.

Ken: Beyond the circus atmosphere of each successive 'revolutionary' claim, what do we basically know about our origins that seems solid?

Holly: Humans share

a common ancestor with chimpanzees between 8-4 million years ago (mya). It

lived in Africa. It may or may not have been bipedal but the evidence right now

indicates it was not. Since that split, for four million years (until about 2

mya), hominin evolution took place exclusively in Africa (the record is largest

from East and South Africa), during which time body size remained fairly small (with

rare exceptions) and human-style bipedal traits accumulate in the skeleton.

Teeth are rather large during that time, but they trend smaller as time passes,

especially the canine. About 3.5 mya a separate lineage splits from the australopiths

and the lineage that ends in us. It’s the robust australopiths who had large

teeth and jaws used for a harder and/or tougher diet than contemporaneous

hominins. The robusts lived only in Africa and disappear around 1 mya. The

first cut marked bone and stone tools show up around 2.5 mya in Ethiopia signalling

a change in hominin behavior/ecology/diet. As we discussed here, some much

earlier cut-marked bones were found at another Ethiopian site 0.8 mya earlier. These

isolated “firsts” are followed by a much more regular and ever-denser record of

tool production and meat-processing after 2 mya. Just after 2 mya we find the

first hominin fossils outside of Africa—in Georgia and Indonesia. The brain

gets slightly larger, but not by much, at this time and the skeleton, by about

1.5 mya is close to ours except for the brain size (which is still about half-three-quarters

of our size), tooth size (still a bit large), and the shoulder anatomy which

doesn’t seem to have the full range of motion of ours (which would mean

throwing wasn’t “modern”). Since the first stone tools appear, there is a fairly

steady increase in technological complexity to the present, although the

Acheulean “handaxe” industry certainly sustains for quite a while (perhaps a

million years) suggesting that big bulky stone bifaces were a lot more useful

than they appear. Alongside the technological development is ever-increasing

body size, with variation present, but the maximum size increases over time.

There is also ever-increasing brain size to the present. And this is all

happening as we find hominins inhabiting distant and diverse landscapes.*

Ken: Or is this [

A. sediba] basically just another specimen, even if it's interesting?

Holly: Nope. It’s not just another specimen. We don’t

have many skeletons let alone skeletons with cranial remains and teeth

associated with them. Let alone more than one skeleton associated, giving us

some idea of variation within a species, or at least a family. These fossils are

truly extraordinary and deserve all the fanfare.

Do all new hominin fossils

deserve so much fanfare? I'm sure answers vary widely person-to-person. Some of

us hyperventilate over half a molar, others could never hear of a fossil their

whole life and die incredibly happy. I don't go ga-ga when stock prices go up,

I don't swoon when I read headlines that Brad dumped Angelina, I don't drop

everything when Marc Jacobs makes new pants, but all reports of those stories

certainly come off as obnoxious as those about new hominin fossils. It's just

show biz. And I'm fine with show biz if it gets people interested in evolution

which can snowball into them learning about evolution. I love that new fossils

even make the news when there are stocks, and celebs, and fashion shows hogging

so much of the attention.

*I left out so many established/cool details because this post is already too long.

7 comments:

I don't know if you read the NY Times coverage, but I was pretty impressed with the article that I read which quoted the authors as well as several other paleo types who observed that these were really cool fossils and applauded the openness with which the authors have shared data but concluded that this doesn't really change anything conclusively.

One quote even alluded to the incredible difficulty in identifying which fossil ancestors are really in our lineage - to the point that we may never totally reconcile it. I doubt that media coverage will ever become as nuanced as we would like, but it is nice to see some nuance.

Definitely.

Thank you, Holly. I have much more to learn from you in this field than what I can challenge, and I like to keep up with this, perhaps for as you say for narcissistic reasons.:)

Anyway, do you really think that there was a remote possibility of that our last common ancestor with chimps "may or may not have been bipedal"? I suppose I see no reason for a reasonable doubt in the conclusion that chimps never had bipedal ancestry.

The consensus right now, based on the available evidence, is that the common ancestors of chimps and humans were not bipedal and that at very soon after the split of the two lineages (around 6 mya) bipedal locomotion appeared. However, of course there are other hypotheses... one being that bipedalism is much older and that African ape ancestors were bipedal and that we are the only ones to remain so, with gorillas, chimps and bonobos evolving knucklewalking. Then there's another one that has knucklewalking as the ancestral locomotion and bipedalism evolved from a knuckle-walking ancestor.

Thank you, Holly. I know that the fossil record indicates various exceptions to maximum parsimony, but I suppose that compelling evidence would be needed to seriously consider that chimps and gorillas had bipedal ancestors. I also would expect knuckle-walking ancestors of humans outside of the chimp lineage. Anyway, I'll try to bring this more into your focus on Australopithecus sediba. Is there any evidence that A. sediba was a knuckle walker? I suppose such evidence would be in the hips and not in the knuckles. Or how could we determine if any Australopithecines were knuckle walkers?

" I know that the fossil record indicates various exceptions to maximum parsimony, but I suppose that compelling evidence would be needed to seriously consider that chimps and gorillas had bipedal ancestors." - Yes and yes, however, that scenario isn't far-fetched at all if you think about how apes move about in the trees. If the common ancestor walked on its palms in the trees and on the ground (and it did), and then bipedal posture was prevalent for a common ancestor, and selection for that remained in our lineage but in others, moving about quadrupedally became important/useful/not horrible again and that posture was knuckle-walking instead of palmigrady ... why not? You can carry things when you walk on your knuckles that you can't carry when you walk on your palms too. These hypotheses are testable with an increasing fossil record.

"Is there any evidence that A. sediba was a knuckle walker?" Not that I've read about. It would have to come from the bones of the hand and wrist and it would be very surprising given there is only maybe evidence for the potential vestiges of such adaptations in much earlier homs. The wrist (carpal) anatomy is rigid without some of the movable joints that we have. Also, when you walk on your knuckles the bones of your fingers and hand are stouter from resisting the forces. There is evidence that it was climbing a great deal (in Kivell et al.'s paper that goes with the several linked above).

Thanks, Holly. After my last post, I eventually recalled that Australopithecines were never known for both bipedalism and knuckle walking, but for both bipedalism and tree climbing. Despite my confusion, you did a great job fielding my reply. :)

Post a Comment