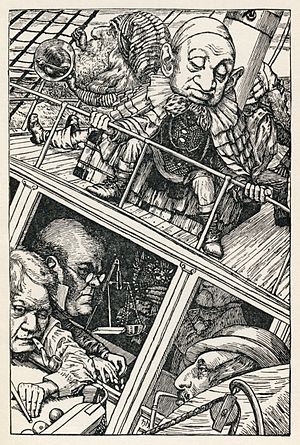

`Just the place for a Snark! I have said it twice:

`Just the place for a Snark! I have said it twice:

- That alone should encourage the crew.

- Just the place for a Snark! I have said it thrice:

- What I tell you three times is true.''

Sometimes this fits our predispositions but often the story is more complex. Often we are chasing after truths about rare causal phenomena, where adequate data are tough or impossible to collect and it is sometimes not even clear what we need to collect.

Do mammograms cause more cancer than they detect, or treatment for tumors that would have regressed on their own? What about dental x-rays or occupational exposures such as, for example, work in a molecular genetics lab that uses radioisotopes for labeling reactions?

Or, to take the story on the CNN website on Tuesday that triggered this post, does mobile-phone usage cause brain cancer? The concern has been around since some early studies about a decade ago, but most subsequent studies have not confirmed the effect. The idea is that a cell phone emits weak electromagnetic radiation that, when held close to the head can cause DNA damage that leads to cancer. Yet, the energy level would seem to be too small to do that, based on what's known about DNA. And some studies (including the one reported this week) claim the additional persuasive kind of evidence that the side of the head the user prefers to listen with is the side that preferentially develops a tumor.

The CNN story reports that a decade-long World Health Organization study of cellphone risk is due out by the end of the year, and that it will claim "significantly increased risk" of some brain tumors. A meta-analysis of 23 different studies, that is, one that unified the separate studies into a single overall analysis, published in The Journal of Clinical Oncology in December, 2008, found a slightly increased risk as well, in the eight studies the authors deemed likely to be the most accurate (that is, they were double-blind, and not funded by mobile phone companies; this is actually true--the studies funded by phone companies in fact found that mobile phone use was slightly protective!).

But even people who defend the idea that cellphones are risky don't deny that there are problems with each of these studies. They are all retrospective, for one thing, which increases the possibility of faulty memory of phone usage, or the amount of head-side preference, and many were too short-term--e.g., six months--to adequately measure risk, since brain tumors generally develop over years, not months. So, even the data from the best of these studies is not conclusive, partly because of the way these studies were designed and partly because if there is a risk from cellphone use, it's small and going to be very difficult to tease out, even with the best of studies.

Other studies of the risks of low-dose radiation have been notoriously plagued by similar issues--yet are important for setting exposure limits to radiation workers, medical patients, etc.

But, if cellphone risk is real, this is a genetic story in that the tumors would be due to some exposed cell by bad luck acquiring the wrong set of mutations that led it to stop obeying 'don't grow' signals. But the changes are inherited from the first brain cell to its descendants in the brain, but not transmitted in the germ line. Of course, and here would be yet another challenge to detect, some individuals might be susceptible because their brain cells have inherited some set of mutations that already lead them part-way down the path to cancer. (These aspects of change and inheritance are major subjects in our book.)

However, the reason the evidence for mobile-phone effects seems implausible to some may (again, if the effects are real) be because the assumption that the cause is DNA damage. Suppose it is some other induced change in cell behavior. Then perhaps the arguments about energy levels are wrong. One might guess what the other types of change might be.....but we are not the ones to do such guessing since that would be far out of what we know anything about.

Still, questions such as these show the elusive nature of making sense of data when the snarks we're trying to catch are elusive.

If the exposure is, from our normal point of view, very very small and hard to estimate, and the outcome very rare, how can we tell? Even a single cancer can be a tragedy for that individual. But do we outlaw mobiles for that?

Like the assertion in the poem, we see the same claim made repeatedly in the media, reporting this study or that. We also see the same denial of the assertion made repeatedly in the media and in some other study. Is repetition a good basis for holding either opinion about such causal claims?

Clearly repetition without evidence is not in itself any kind of criterion. Anyone can say anything (as the group leader did in regard to the snark). For well-known statistical reasons, even a large study can fail to detect a small effect, with there being no design problems or fault on the part of the scientist. Flip a coin twice: though the true probability of a Heads is 1/2, many times you'll get two heads or two tails.

Many important problems in biology are like this and because of the seriousness of the outcome, radiation exposures are among them. But we're besieged with claims about this or that risk factor, where the risks are thought to be substantially more than with cellphones, and yet we can't seem to get a definitive answer even then.

Evolution works slowly, or so it seems. So slowly that mutation is very rare, selective differences very small, and life's conditions highly irregular. As with other small causal factors and rare or very slow effects, it is difficult to know what evidence counts the most. It presents a sobering challenge to science. And lots of room for strong, if often emotional rather than factually solid debate.

After all, it turned out that the snark was a boojum, you see!

-Ken and Anne

No comments:

Post a Comment