In what sense--what scientific sense--does the future resemble the past? Or perhaps, to what extent does it? Can we know? If we can't, then what credence for future prediction can we give to results of studies today, necessarily from the past experience of current samples? Similarly, in what sense can we extrapolate findings on this sample to some other sample or population? If these questions are not easily answerable (indeed if they are answerable at all!), then much of current, and currently very widespread and expensive science, is at best of unclear, questionable value.

We can look at these issues in terms of a couple of standard aspects of science: the relationship between induction and deduction; and the idea of replicability. Induction and deduction basically come from the Enlightenment time in western history, when it was found in a formal sense that the world of western science--which at that time meant physical science--followed universal 'laws' of Nature. At that time, life itself was generally excluded from this view, not least because it was believed to be the result of ad hoc creation events by God.

The induction--deduction problem

-----------------

Some terminology: I will make an important distinction between two terms. By induction I mean drawing a conclusion from specific observed data (e.g., estimating some presumed causal parameter's value). Essentially, this means inferring a conclusion from the past, from events that have already occurred. But often what we want to do is to predict the future. We do that, often implicitly, by equating observed past values as estimates of causal parameters, that apply generally and therefore to the future; I refer to that predictive process, derived from observed data, as deduction. So, for example, if I flip a coin 10 times and get 5 Heads, I assume that this is somehow built into the very nature of coin-flipping so that the probability of Heads on any future flip is 0.5 (50%).

-----------------

If we can assume that induction implies deduction, then what we observe in our present or past observations will persist so that we can predict it in the future. In a law-like universe, if we are sampling properly, this will occur and we generally assume this means with complete precision if we had perfect measurement (here I speculate, but I think that quantum phenomena at the appropriate scale have the same universally parametric properties).

Promises like 'precision genomic medicine', which I think amount to culpably public deceptions, effectively equate induction with deduction: we observe some genomic elements associated in some statistical way with some outcome, and assume that the same genome scores will similarly predict the future of people decades from now. There is no serious justification for this assumption at present, nor quantification of by how much there might be errors in assuming the predictive power of past observations, in part because mutations and lifestyle clearly have major effects, but especially because these are unpredictable--even in principle. Indeed, there is another, much deeper problem of a similar kind, that has gotten recent--but to me often quite naive attention: replicability.

The replicability problem

Studies, perhaps especially in social and behavioral fields, report findings that others cannot replicate. This is being interpreted as suggesting that (ignoring the rare outright fraud), there is some problem with our decision-making criteria, other forms of bias, or poor study designs. Otherwise, shouldn't studies of the same question agree? There has been a call for the investigators involved to improve their statistical analysis (i.e., keep buying the same software!! but use it better), report negative results, and so on.

But this is potentially, and I think fundamentally, naive. It assumes that such study results should be replicable. It assumes, as I would put it, that at the level of interest, life = physics. This is, I believe not just wrong but fundamentally so.

The assumption of replicability is not really different from equating induction to deduction, except in some subtle way applied to a more diverse set of conditions. Induction of genomic-based disease risk is done on a population like, say, case-control samples, and then applied to the same population in terms of its current members' future disease risks. But we know very well that different genotypes are found in different populations, so it is not clear what degree of predictability we should, or can, assume.

Replicability is similar except that in general a result is assumed to apply across populations or samples, not just to the same sample's future. That is, I think, an even broader assumption than the genomics-precision promise that does, at least nominally, now recognize population differences.

The real, the deeper problem is that we have absolutely no reason to expect any particular degree of replicability between samples for these kinds of things. Evolution is about variation, locally responsive and temporary, and that applies to social behavior as well. We know that 'distance' or difference accumulates (generally) gradually over time and separation as a property of cultural as well as biological evolution. The same obviously applies even more to psychological and sociological samples and inferences from them.

Not only is it silly to think that samples of, say, this year's college seniors at X University will respond to questionnaires in the same way as samples of some other class or university or beyond. Of course, college students come cheap to researchers, and they're convenient. But they are not 'representative' in the replicability sense except by some sort of rather profound assumption. This is obvious, yet it is a tacit concept of very much research (biological, psychological, and sociological).

Even social scientists acknowledge the local and temporary nature of many of the things they investigate, because the latter are affected by cultural and historical patterns, fads, fashions, and so much more. Indeed, the idea of replicability is to me curious to begin with. Thus, a study that fails to replicate some other study may not reflect failings in either, and the idea that we should replicate in this kind of way is a carryover of physics envy. Perhaps in many situations, a replication result is what should be examined most closely! The social and even biological realms are simply not as 'Newtonian', or law-like, as is the real physical realm in which our notions of science--especially the very idea of a law-like replicability, arose. Not only is failure to replicate not necessarily suspect at all, but replicability should not generally be assumed. Or, put an other way, a claim that replicability is to be expected is a strong claim about Nature that requires very strong evidence!

This raises the very deep problem that in the absence of replicability assumptions, we don't know what to expect of the next study, after we've done the first.....or is this a justification for just keeping the same studies going (and funded) indefinitely? That's of course the very rewarding game being played in genomics.

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Monday, November 19, 2018

It is unethical to teach evolution, no matter the organism, without confronting racism and sexism

People say we’re the storytelling ape. I hear that. Though conjuring fiction is beyond me, and I only remember the worst punchlines, I love trading stories and so do you. Storytelling is a definitively human trait. But if stories make us human, what went wrong with the mother of them all?

Human origins should be universally cherished but it’s not even universally known. It just doesn’t appeal to most people. This goes far beyond religion. Human evolution hasn’t caught on despite it being over 150 years old. Where it has, it’s subversive or offensive. We have a problem. How could my life be subversive or offensive. How could yours?

Whether or not we evolved to tell stories, the one about where we came from should be beloved, near and dear to our hearts, not cold, clinical, and pedantic, not repulsive or embarrassing, not controversial, racist, sexist and anti-theist, not merely “survival of the fittest,” end of story, not something that only pertains to the world’s champions of wealth or babymaking. We deserve so much better. We deserve a sprawling, heart-thumping, face-melting epic, inspiring its routine telling and retelling. It’s time for a human evolution that’s fit for all humankind.

Such a human evolution requires a new narrative, both hyper-sensitive to the power of narrative and rooted in science that is light years ahead of Victorian dogma. This is the antidote to a long history of weaponizing human nature against ourselves. Our 45th president credits the survival-of-the-fittest brand of human evolution for his success over less kick-ass men in business and in bed. Pick-up artists and men’s rights activists, inspired by personalities like Jordan Peterson, use mistaken evolutionary thinking to justify their sexism and misogyny. Genetic and biological determinism have a stranglehold on the popular imagination, where evolution is frequently invoked to excuse inequity, like in the notorious Google Memo. Public intellectuals like David Brooks and Jon Haidt root what seems like every single observation of 2018 in tropes from Descent of Man. And there's the White House memo that unscientifically defines biological sex. Evolution is all wrapped up in white supremacy and a genetically-destined patriarchy. This is not evolution. And this is not my evolution. I know you're nodding your head along with me.

Without alternative perspectives, who can blame so many folks for out-right avoiding evolutionary thinking? We must lift the undeserved stigma on our species' origins story and rip it away from those who would perpetuate its abuses.

It took me a while to get to this point, to have this view that I wish I'd had from the very beginning. No one should feel defensive in reaction to my opinion, which is...

Evolution educators—even if sticking to E.coli, fruit flies, or sticklebacks—must confront the ways that evolutionary science has implicitly undergirded and explicitly promoted, or has naively inspired so many racist, sexist, and otherwise harmful beliefs and actions. We can no longer arm students with the ideas that have had harmful sociocultural consequences without addressing them explicitly, because our failure to do so effectively is the primary reason these horrible consequences exist. The worst of all being a human origins that refuses humanity.

So many of us are still thinking and teaching from the charged tradition of demonstrating that evolution is true. Thanks to everyone's hard work, it is undeniably true. Now we must go beyond this habit of reacting to creationism and instead react to a problem that is just as old but is far more urgent because it actually affects human well-being.

Bad evolutionary thinking and its siblings, genetic determinism and genetic essentialism, are used to justify civil rights restrictions, human rights violations, white supremacy, and the patriarchy. And as a result, evolution is avoided and unclaimed by scholars, students, and their communities who know this all too well.

In Why be against Darwin? Creationism, racism, and the roots of anthropology,* Jon Marks explains how early anthropologists, in the immediate wake of Darwin's ideas, faced a dilemma. If they were to continue as if there were a "psychic unity of (hu)mankind" then they felt compelled to reject an evolution which was being championed by some influential scientific racists. Marks writes, "So either you challenge the authority of the speaker to speak for Darwinism or you reject the program of Darwinism." Anyone who knows someone who's not a fan of evolution, knows that the latter option is a favorite still today. And it's not creationism and it's not science denial. It's the rejection of what we know to be an outdated and tainted notion of evolution. No one can update and clean up evolution as powerfully as we can if we do it ourselves, right there, in the classroom.

We are teaching more and more people evolution which may be exciting but only if we are equally as energetic in our confrontation of its sordid past. I can say this without attracting any indignation (right?) because of the fact that evolution has a sordid present.

Let's put that to an end.

Here I offer some general suggestions for how to do that and I'm speaking to all of us, whether we teach a course dedicated to human origins and evolution, whether we teach a course dedicated to evolution and only cover humans for part of it, whether we teach a course dedicated to evolution but exclude humans entirely... because we all have to actively fix this. Learners will apply evolutionary thinking to humans, whether or not your focal organisms are human. Making rules in one domain and transferring them to new ones is humanity's jam. Eugenics is proof that our jam can go rancid.

And while we're actively disassociating the reality of evolution (which is just a synonym for 'nature' and for 'biology') from all the shitty things humans do in its name, we can help make it more personal as we all deserve our origins story to be. We deserve a human origins we can embrace.

Model that personal satisfaction in thinking evolutionarily about your own life. Don't be afraid to bring the humanities into your evolution courses.

Choose examples and activities focused on the evolution of the human body or focused on the unity of the species. Go there if you don't already. Here are some awesome lesson plans: http://humanorigins.si.edu/education/teaching-evolution-through-human-examples

Guide students in composing scientifically sourced and scientifically sound origins stories for their favorite things in life, like their friends or pizza (maybe by tracking down the origins of wheat, lactase persistence, cooking, teeth, or even way back to the first eaters of anything at all).

For actively dismantling evolution's racist/etc past and present, may I suggest checking out and maybe assigning (+ the Marks article linked above):

10 Facts about human variation by Marks

Is Science Racist? by Marks

Racing around, getting nowhere* by Weiss (fellow mermaid) and Fullerton

A Dangerous Idea: Eugenics and the American Dream (film)

If you are feeling under-prepared or uncomfortable going beyond biology in your course, find a colleague who can help out or do it entirely for you. If they're on campus, pick their brains about assignments or activities, or ask them for a guest lecture. If they're not on campus, invite them to campus or connect them to your classroom via Skype. There are all stripes of anthropologists (and there are also historians) who are comfortable and more than happily willing to help you cover evolution as it should be, which is to explicitly include its sociocultural context and consequences.

*This article is open access but if for some reason you still cannot access it, just email me at holly_dunsworth@uri.edu and I will send you the pdf.

Additional Resources of Relevance...

Human origins should be universally cherished but it’s not even universally known. It just doesn’t appeal to most people. This goes far beyond religion. Human evolution hasn’t caught on despite it being over 150 years old. Where it has, it’s subversive or offensive. We have a problem. How could my life be subversive or offensive. How could yours?

Whether or not we evolved to tell stories, the one about where we came from should be beloved, near and dear to our hearts, not cold, clinical, and pedantic, not repulsive or embarrassing, not controversial, racist, sexist and anti-theist, not merely “survival of the fittest,” end of story, not something that only pertains to the world’s champions of wealth or babymaking. We deserve so much better. We deserve a sprawling, heart-thumping, face-melting epic, inspiring its routine telling and retelling. It’s time for a human evolution that’s fit for all humankind.

Such a human evolution requires a new narrative, both hyper-sensitive to the power of narrative and rooted in science that is light years ahead of Victorian dogma. This is the antidote to a long history of weaponizing human nature against ourselves. Our 45th president credits the survival-of-the-fittest brand of human evolution for his success over less kick-ass men in business and in bed. Pick-up artists and men’s rights activists, inspired by personalities like Jordan Peterson, use mistaken evolutionary thinking to justify their sexism and misogyny. Genetic and biological determinism have a stranglehold on the popular imagination, where evolution is frequently invoked to excuse inequity, like in the notorious Google Memo. Public intellectuals like David Brooks and Jon Haidt root what seems like every single observation of 2018 in tropes from Descent of Man. And there's the White House memo that unscientifically defines biological sex. Evolution is all wrapped up in white supremacy and a genetically-destined patriarchy. This is not evolution. And this is not my evolution. I know you're nodding your head along with me.

Without alternative perspectives, who can blame so many folks for out-right avoiding evolutionary thinking? We must lift the undeserved stigma on our species' origins story and rip it away from those who would perpetuate its abuses.

**

It took me a while to get to this point, to have this view that I wish I'd had from the very beginning. No one should feel defensive in reaction to my opinion, which is...

Evolution educators—even if sticking to E.coli, fruit flies, or sticklebacks—must confront the ways that evolutionary science has implicitly undergirded and explicitly promoted, or has naively inspired so many racist, sexist, and otherwise harmful beliefs and actions. We can no longer arm students with the ideas that have had harmful sociocultural consequences without addressing them explicitly, because our failure to do so effectively is the primary reason these horrible consequences exist. The worst of all being a human origins that refuses humanity.

|

| Make this history ancient history. We've waited too long. (image: Marks, 2012) |

So many of us are still thinking and teaching from the charged tradition of demonstrating that evolution is true. Thanks to everyone's hard work, it is undeniably true. Now we must go beyond this habit of reacting to creationism and instead react to a problem that is just as old but is far more urgent because it actually affects human well-being.

Bad evolutionary thinking and its siblings, genetic determinism and genetic essentialism, are used to justify civil rights restrictions, human rights violations, white supremacy, and the patriarchy. And as a result, evolution is avoided and unclaimed by scholars, students, and their communities who know this all too well.

In Why be against Darwin? Creationism, racism, and the roots of anthropology,* Jon Marks explains how early anthropologists, in the immediate wake of Darwin's ideas, faced a dilemma. If they were to continue as if there were a "psychic unity of (hu)mankind" then they felt compelled to reject an evolution which was being championed by some influential scientific racists. Marks writes, "So either you challenge the authority of the speaker to speak for Darwinism or you reject the program of Darwinism." Anyone who knows someone who's not a fan of evolution, knows that the latter option is a favorite still today. And it's not creationism and it's not science denial. It's the rejection of what we know to be an outdated and tainted notion of evolution. No one can update and clean up evolution as powerfully as we can if we do it ourselves, right there, in the classroom.

We are teaching more and more people evolution which may be exciting but only if we are equally as energetic in our confrontation of its sordid past. I can say this without attracting any indignation (right?) because of the fact that evolution has a sordid present.

Let's put that to an end.

Here I offer some general suggestions for how to do that and I'm speaking to all of us, whether we teach a course dedicated to human origins and evolution, whether we teach a course dedicated to evolution and only cover humans for part of it, whether we teach a course dedicated to evolution but exclude humans entirely... because we all have to actively fix this. Learners will apply evolutionary thinking to humans, whether or not your focal organisms are human. Making rules in one domain and transferring them to new ones is humanity's jam. Eugenics is proof that our jam can go rancid.

And while we're actively disassociating the reality of evolution (which is just a synonym for 'nature' and for 'biology') from all the shitty things humans do in its name, we can help make it more personal as we all deserve our origins story to be. We deserve a human origins we can embrace.

Model that personal satisfaction in thinking evolutionarily about your own life. Don't be afraid to bring the humanities into your evolution courses.

Choose examples and activities focused on the evolution of the human body or focused on the unity of the species. Go there if you don't already. Here are some awesome lesson plans: http://humanorigins.si.edu/education/teaching-evolution-through-human-examples

Guide students in composing scientifically sourced and scientifically sound origins stories for their favorite things in life, like their friends or pizza (maybe by tracking down the origins of wheat, lactase persistence, cooking, teeth, or even way back to the first eaters of anything at all).

For actively dismantling evolution's racist/etc past and present, may I suggest checking out and maybe assigning (+ the Marks article linked above):

10 Facts about human variation by Marks

Is Science Racist? by Marks

Racing around, getting nowhere* by Weiss (fellow mermaid) and Fullerton

A Dangerous Idea: Eugenics and the American Dream (film)

If you are feeling under-prepared or uncomfortable going beyond biology in your course, find a colleague who can help out or do it entirely for you. If they're on campus, pick their brains about assignments or activities, or ask them for a guest lecture. If they're not on campus, invite them to campus or connect them to your classroom via Skype. There are all stripes of anthropologists (and there are also historians) who are comfortable and more than happily willing to help you cover evolution as it should be, which is to explicitly include its sociocultural context and consequences.

*This article is open access but if for some reason you still cannot access it, just email me at holly_dunsworth@uri.edu and I will send you the pdf.

Additional Resources of Relevance...

There's

no such thing as a 'pure' European—or anyone else – Gibbons (Science)

A lot of

Southern whites are a little bit black – Ingraham (Washington Post)

From

the Belgian Congo to the Bronx Zoo (NPR)

A

True and Faithful Account of Mr. Ota Benga the Pygmy, Written by M. Berman,

Zookeeper – Mansbach

Are

humans hard-wired for racial prejudice?

- Sapolsky (LA Times)

Colonialism and

narratives of human origins in Asia and Africa— Athreya

and Ackerman

Frederick

Douglass’s fight against scientific racism – Herschthal (NYT)

The unwelcome

revival of race science—Evans (The

Guardian)

#WakandanSTEM:

Teaching the evolution of skin color—Lasisi

For Decades, Our

Coverage Was Racist. To Rise Above Our Past, We Must Acknowledge It: We asked a

preeminent historian to investigate our coverage of people of color in the U.S.

and abroad. Here’s what he found—Goldberg (NatGeo) https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/04/from-the-editor-race-racism-history/

There’s No

Scientific Basis for Race—It's a Made-Up Label: It's been used to define and

separate people for millennia. But the concept of race is not grounded in

genetic—Kolbert (NatGeo) https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/04/race-genetics-science-africa/

Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death

Crisis - Villarosa (The New York Times) https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/magazine/black-mothers-babies-death-maternal-mortality.html

The labor of racism –Davis (Anthrodendum) https://anthrodendum.org/2018/05/07/the-labor-of-racism/

Being black in

America can be hazardous to your health – Khazan (The Atlantic) https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/07/being-black-in-america-can-be-hazardous-to-your-health/561740/

White People Are

Noticing Something New: Their Own Whiteness—Bazelon (The New York Times) https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/13/magazine/white-people-are-noticing-something-new-their-own-whiteness.html

Ancestry Tests

Pose a Threat to Our Social Fabric: Commercial DNA testing isn’t just harmless

entertainment. It’s keeping alive ideas that deserve to die – Terrell (Sapiens)

https://www.sapiens.org/technology/dna-test-ethnicity/

Surprise!

Africans are not all the same (or why we need diversity in science) – Lasisi

Why white

supremacists are chugging milk (and why geneticists are alarmed) – Harmon (NYT)

Everyday

discrimination raises womens blood pressure – Yong (The Atlantic)

How the alt-right’s sexism lures men into white supremacy –

Romano (Vox)

Sex

Redefined – Ainsworth (Nature)

Peace

Among Primates – Sapolsky (The Greater Good)

Against Human

Nature—Ingold

Thursday, November 8, 2018

The horseshoe crab and the barnacle: induction vs deduction in evolution

Charles Darwin had incredible patience. After his many-year, global voyage on the HMS Beagle, he nestled in at Down House, where he was somehow able to stay calm and study mere barnacles to an endless extent (and to write 4--four--books on these little creatures). Who else would have had the obsessive patience (or independent wealth and time on one's hands) to do such a thing?

Darwin's meticulous work and its context in his life and thinking are very well described in Rebecca Stott's compelling 2003 book, Darwin and the Barnacle, which I highly recommend, as well as the discussion of these topics in Desmond and Moore's 1991 Darwin biography, The Life of a Tormented Evolutionist. These are easier, for seeing the points I will describe here, than plowing through Darwin's detailed own tomes (which, I openly confess, I have only browsed). His years of meticulous barnacle study raised many questions in Darwin's mind, about how species acquire their variation, and his pondering this eventually led to his recognition of 'evolution' as the answer, which he published only years later, in 1859, in his Origin of Species.

Darwin was, if anything, a careful and cautious person, and not much given to self-promotion. His works are laden with appropriate caveats including, one might surmise, careful defenses lest he be found to have made interpretive or theoretical mistakes. Yet he dared make generalizations of the broadest kind. It was his genius to see, in the overwhelming variation in nature, the material for understanding how natural processes, rather than creation events, led to the formation of new species. This was implicitly true of his struggle to understand the wide variation within and among species of barnacles, variation that enabled evolution, as he later came to see. Yet the same variation provided a subtle trap: it allowed escape from accusations of undocumented theorizing, but was so generic that in a sense it made his version of a theory of evolution almost unfalsifiable in principle.

But, in a subtle way, Mr Darwin, like all geniuses, was also a product of his time. I think he took an implicitly Newtonian, deterministic view of natural selection. As he said, selection could detect the 'smallest grain in the balance' [scale] of differences among organisms, that is, could evaluate and screen the tiniest amount of variation. He had, I think, only a rudimentary sense of probability; while he often used the word 'chance' in the Origin, it was in a very casual sense, and I think that he did not really think of chance or luck (what we call genetic drift) as important in evolution. This I would assert is widely persistent, if largely implicit, today.

One important aspect of barnacles to which Darwin paid extensive attention was their sexual diversity. In particular, many species were hermaphroditic. Indeed, in some species he found small, rudimentary males literally embedded for life within the body of the female. Other species were more sexually dichotomous. These patterns caught Darwin's attention. In particular, he viewed this transect in evolutionary time (our present day) as more than just a catalog of today, but also as a cross-section of tomorrow. He clearly thought that what we saw today among barnacle species represented the path that other species had taken towards becoming the fully sexually dichotomous (independent males and females) in some species today: the intermediates were on their way to these subsequent stages.

This is a deterministic view of selection and evolution: "an hermaphrodite species must pass into a bisexual species by insensibly small stages" from single organisms having both male and female sex organs to the dichotomous state of separate males and females (Desmond and Moore: 356-7).

But what does 'must pass' mean here? Yes, Darwin could array his specimens to show these various types of sexual dimorphism, but what would justify thinking of them as progressive 'stages'? What latent assumption is being made? It is to think of the different lifestyles as stages along a path leading to some final inevitable endpoint.

If this doesn't raise all sorts of questions in your mind, why not? Why, for example, are there any intermediate barnacle species here today? Over the eons of evolutionary time why haven't all of them long ago reached their final, presumably ideal and stable state? What justifies the idea that the species with 'intermediate' sexuality in Darwin's collections are not just doing fine, on their way to no other particular end? Is something wrong with their reproduction? If so, how did they get here in the first place? Why are there so many barnacle species today with their various reproductive strategies (states)?

Darwin's view was implicitly of the deterministic nature of selection--heading towards a goal which today's species show in their various progressive stages. His implicit view can be related to another, current controversy about evolution.

Rewinding the tape

There has for many recent decades been an argument about the degree of directedness or, one might say, predictability in evolution. If evolution is the selection among randomly generated mutational variants for those whose survival and reproduction are locally, at a given time favored, then wouldn't each such favored path be unique, none really replicable or predictable?

Not so, some biologists have argued! Their view is essentially that environments are what they are, and will systematically--and thus predictably--favor certain kinds of adaptation. There is, one might quip, only one way to make a cake in a particular environment. Different mutations may arise, but only those that lead to cake-making will persist. Thus, if we could 'rewind the tape' of evolution and go back to way back when, and start again, we would end up with the same sorts of adaptations that we see with the single play of the tape of life that we actually have. There would, so to speak, always be horseshoe crabs, even if we started over. Yes, yes, some details might differ, but nothing important (depending, of course, on how carefully you look--see my 'Plus ça ne change pas', Evol. Anthropol, 2013, a point others have made, too).

Others argue that evolution is so rooted in local chance and contingency, that there would be no way to predict the details of what would evolve, could we start over at some point. Yes, there would be creatures in each local niche, and there would be similarities to the extent that what we would see today would have to have been built from what genetic options were there yesterday, but there the similarity would end.

Induction, deduction, and the subtle implications of the notion of 'intermediate' forms

Stott's book, Darwin and the Barnacle, discusses Darwin's work in terms of the presumed intermediate barnacle stages he found. But the very use of such terms carries subtle implications. It conflates induction with deduction, it assumes what is past will be repeated. It makes of evolution what Darwin also made of it: a deterministic, force-like phenomenon. Indeed, it's not so different from a form of creationism.

This has deeper implications. Among them are repeatability of environments and genomes, at least to the extent that their combination in local areas--life, after all, operates strictly on local areas--will be repeated elsewhere and else-times. Only by assuming not only the repeatability of environments but also of genomic variation, can one see in current states of barnacle species today stages in a predictable evolutionary parade. The inductive argument is the observation of what happened in the past, and the deductive argument is that what we see is intermediate, on its way to becoming what some present-day more 'advanced' stage is like.

This kind of view, which is implicitly and (as with Darwin) sometimes explicitly invoked, is that we can use the past to predict the future. And yet we routinely teach that evolution is by its essential nature locally ad hoc and contingent, based on random mutations and genetic drift--and not driven by any outside God or other built-in specific creative force.

And 'force' seems to be an apt word here.

The idea that a trait found in fossils, that was intermediate between some more primitive state and something seen today, implies that a similar trait today could be an 'intermediate stage' today for a knowable tomorrow, conflates inductive observation with deductive prediction. It may indeed do so, but we have no way to prove it and usually scant reason to believe it. Instead, equating induction with deduction tacitly assumes, usually without any rigorous justification, that life is a deductive phenomenon like gravity or chemical reactions.

The problem is serious: the routine equating of induction with deduction gives a false idea about how life works, even in the short-term. Does a given genotype, say, predict a particular disease in someone who carries it, because we find that genotype associated with affected patients today? This may indeed be so, especially if a true causal reason is known; but it cannot be assumed to be. We know this from well-observed recent history: Secular trends in environmental factors with disease consequences have indeed been documented, meaning that the same genotype is not always associated with the same risk. There is no guarantee of a future repetition, not even in principle.

Darwin's worldview

Darwin was, in my view, a Newtonian in his view. That was the prevailing science ethos in his time. He accepted 'laws' of Nature and their infinitesimally precise action. That Nature was law-like was a prevailing, and one may say fashionable view at the time. It was also applied to social evolution, for example, as in Marx's and Engels' view of the political inevitability of socialism. That barnacles can evolve various kinds of sexual identities and arrangements doesn't mean any of what Darwin observed in them was on the way to full hermaphrodism or even later to fully distinct sexes...or, indeed, to any particular state of sexuality. But if you have a view like his, seeing the intermediate stages even contemporaneously, would reinforce the inevitabilistic aspect of a Newtonian perspective, and seemingly justify using induction to make deductions.

Even giants like Darwin are products of their times, as all we peons are. We gain comfort from equating deduction with induction, that the past we can observe allows us to predict the future. That makes it comfortingly safe to make assertions, the feeling that we understand the complex environment in which we must wend our way through life. But in science, at least, we should know the emptiness of the equation of the past with the future. Too bad we can't seem to see further.

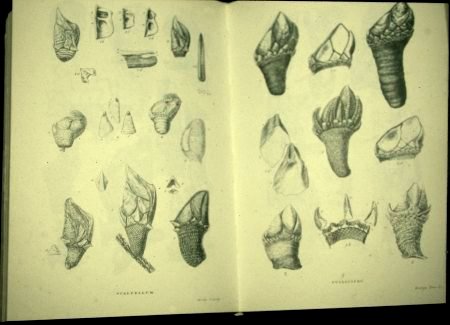

|

| From Darwin's books on barnacles (web image capture) |

Darwin was, if anything, a careful and cautious person, and not much given to self-promotion. His works are laden with appropriate caveats including, one might surmise, careful defenses lest he be found to have made interpretive or theoretical mistakes. Yet he dared make generalizations of the broadest kind. It was his genius to see, in the overwhelming variation in nature, the material for understanding how natural processes, rather than creation events, led to the formation of new species. This was implicitly true of his struggle to understand the wide variation within and among species of barnacles, variation that enabled evolution, as he later came to see. Yet the same variation provided a subtle trap: it allowed escape from accusations of undocumented theorizing, but was so generic that in a sense it made his version of a theory of evolution almost unfalsifiable in principle.

But, in a subtle way, Mr Darwin, like all geniuses, was also a product of his time. I think he took an implicitly Newtonian, deterministic view of natural selection. As he said, selection could detect the 'smallest grain in the balance' [scale] of differences among organisms, that is, could evaluate and screen the tiniest amount of variation. He had, I think, only a rudimentary sense of probability; while he often used the word 'chance' in the Origin, it was in a very casual sense, and I think that he did not really think of chance or luck (what we call genetic drift) as important in evolution. This I would assert is widely persistent, if largely implicit, today.

One important aspect of barnacles to which Darwin paid extensive attention was their sexual diversity. In particular, many species were hermaphroditic. Indeed, in some species he found small, rudimentary males literally embedded for life within the body of the female. Other species were more sexually dichotomous. These patterns caught Darwin's attention. In particular, he viewed this transect in evolutionary time (our present day) as more than just a catalog of today, but also as a cross-section of tomorrow. He clearly thought that what we saw today among barnacle species represented the path that other species had taken towards becoming the fully sexually dichotomous (independent males and females) in some species today: the intermediates were on their way to these subsequent stages.

This is a deterministic view of selection and evolution: "an hermaphrodite species must pass into a bisexual species by insensibly small stages" from single organisms having both male and female sex organs to the dichotomous state of separate males and females (Desmond and Moore: 356-7).

But what does 'must pass' mean here? Yes, Darwin could array his specimens to show these various types of sexual dimorphism, but what would justify thinking of them as progressive 'stages'? What latent assumption is being made? It is to think of the different lifestyles as stages along a path leading to some final inevitable endpoint.

If this doesn't raise all sorts of questions in your mind, why not? Why, for example, are there any intermediate barnacle species here today? Over the eons of evolutionary time why haven't all of them long ago reached their final, presumably ideal and stable state? What justifies the idea that the species with 'intermediate' sexuality in Darwin's collections are not just doing fine, on their way to no other particular end? Is something wrong with their reproduction? If so, how did they get here in the first place? Why are there so many barnacle species today with their various reproductive strategies (states)?

Darwin's view was implicitly of the deterministic nature of selection--heading towards a goal which today's species show in their various progressive stages. His implicit view can be related to another, current controversy about evolution.

Rewinding the tape

There has for many recent decades been an argument about the degree of directedness or, one might say, predictability in evolution. If evolution is the selection among randomly generated mutational variants for those whose survival and reproduction are locally, at a given time favored, then wouldn't each such favored path be unique, none really replicable or predictable?

Not so, some biologists have argued! Their view is essentially that environments are what they are, and will systematically--and thus predictably--favor certain kinds of adaptation. There is, one might quip, only one way to make a cake in a particular environment. Different mutations may arise, but only those that lead to cake-making will persist. Thus, if we could 'rewind the tape' of evolution and go back to way back when, and start again, we would end up with the same sorts of adaptations that we see with the single play of the tape of life that we actually have. There would, so to speak, always be horseshoe crabs, even if we started over. Yes, yes, some details might differ, but nothing important (depending, of course, on how carefully you look--see my 'Plus ça ne change pas', Evol. Anthropol, 2013, a point others have made, too).

Others argue that evolution is so rooted in local chance and contingency, that there would be no way to predict the details of what would evolve, could we start over at some point. Yes, there would be creatures in each local niche, and there would be similarities to the extent that what we would see today would have to have been built from what genetic options were there yesterday, but there the similarity would end.

Induction, deduction, and the subtle implications of the notion of 'intermediate' forms

Stott's book, Darwin and the Barnacle, discusses Darwin's work in terms of the presumed intermediate barnacle stages he found. But the very use of such terms carries subtle implications. It conflates induction with deduction, it assumes what is past will be repeated. It makes of evolution what Darwin also made of it: a deterministic, force-like phenomenon. Indeed, it's not so different from a form of creationism.

This has deeper implications. Among them are repeatability of environments and genomes, at least to the extent that their combination in local areas--life, after all, operates strictly on local areas--will be repeated elsewhere and else-times. Only by assuming not only the repeatability of environments but also of genomic variation, can one see in current states of barnacle species today stages in a predictable evolutionary parade. The inductive argument is the observation of what happened in the past, and the deductive argument is that what we see is intermediate, on its way to becoming what some present-day more 'advanced' stage is like.

This kind of view, which is implicitly and (as with Darwin) sometimes explicitly invoked, is that we can use the past to predict the future. And yet we routinely teach that evolution is by its essential nature locally ad hoc and contingent, based on random mutations and genetic drift--and not driven by any outside God or other built-in specific creative force.

And 'force' seems to be an apt word here.

The idea that a trait found in fossils, that was intermediate between some more primitive state and something seen today, implies that a similar trait today could be an 'intermediate stage' today for a knowable tomorrow, conflates inductive observation with deductive prediction. It may indeed do so, but we have no way to prove it and usually scant reason to believe it. Instead, equating induction with deduction tacitly assumes, usually without any rigorous justification, that life is a deductive phenomenon like gravity or chemical reactions.

The problem is serious: the routine equating of induction with deduction gives a false idea about how life works, even in the short-term. Does a given genotype, say, predict a particular disease in someone who carries it, because we find that genotype associated with affected patients today? This may indeed be so, especially if a true causal reason is known; but it cannot be assumed to be. We know this from well-observed recent history: Secular trends in environmental factors with disease consequences have indeed been documented, meaning that the same genotype is not always associated with the same risk. There is no guarantee of a future repetition, not even in principle.

Darwin's worldview

Darwin was, in my view, a Newtonian in his view. That was the prevailing science ethos in his time. He accepted 'laws' of Nature and their infinitesimally precise action. That Nature was law-like was a prevailing, and one may say fashionable view at the time. It was also applied to social evolution, for example, as in Marx's and Engels' view of the political inevitability of socialism. That barnacles can evolve various kinds of sexual identities and arrangements doesn't mean any of what Darwin observed in them was on the way to full hermaphrodism or even later to fully distinct sexes...or, indeed, to any particular state of sexuality. But if you have a view like his, seeing the intermediate stages even contemporaneously, would reinforce the inevitabilistic aspect of a Newtonian perspective, and seemingly justify using induction to make deductions.

Even giants like Darwin are products of their times, as all we peons are. We gain comfort from equating deduction with induction, that the past we can observe allows us to predict the future. That makes it comfortingly safe to make assertions, the feeling that we understand the complex environment in which we must wend our way through life. But in science, at least, we should know the emptiness of the equation of the past with the future. Too bad we can't seem to see further.