One argument that IQ (here, we let that stand for whatever is measured, without making any supportive judgments that, or when and where it is an appropriate measure of something). Heritability of IQ is not-trivial, generally estimated to be around 80%. The remaining 20% is 'environment', and measurement error and the like.

|

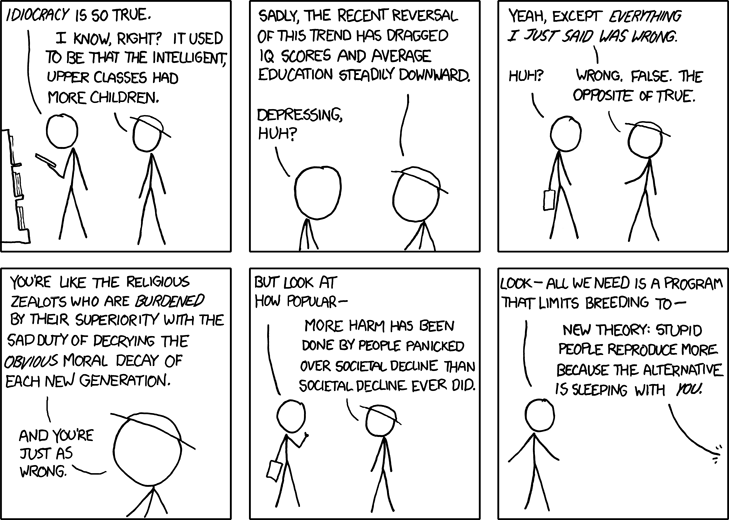

| xkcd: Idiocracy |

Previous studies had shown the tremendous advantage that early exposure to language and complex concepts has on later development, and that means later school success, and that means higher IQ test achievement. Prior work showed that by age 3, children from privileged professional families had heard millions more words spoken than children from unpriviliged families. They also had heard many different words spoken and learned their use. Now, the NY Times reports that this difference can be detected even by or before age 2. Samples were small but the study reinforces the idea that very early experience is telling throughout later life.

So what?

Those who see important group differences in IQ are going to defend their viewpoint by saying that they know very well about environmental variation and take that into account but that early experiences cannot obscure the entire group difference. We don't happen to agree, and this is clearly a matter of personal politics all round, but there are a couple of questions that are fair to ask.

First, is it possible that the actual heritability of the measure is much lower than its estimates? If social class is correlated in families, say by neighborhood, race, or education etc., then this can inflate heritability estimates, showing similar values for similar reasons, in professional as well as lower SES families. This is why adoption studies are often used to show the true heritability, but even there there has been evidence of SES correlation in adoptions.

Secondly, if SES inequality were removed from the picture, the overall heritability might stay the same but there would be no difference of the average and far less variance (variation among individuals) among what were previously very different SES groups.

Third, education policy strives and presumably would strive even harder, to standardize what children are taught from birth on up. They'd be taught or exposed to what our society values, be it vocabulary or mathematics or music or sports. IQ test scores could increase steadily, as they have done for the past several decades, by making the most of everyone's inherited abilities.

There will always be those who are unusual on this or any other kind of value-score system. There will be those who are seriously impaired or seriously gifted, however the neural mechanism works. But the issues of group differences would largely if not entirely disappear; there will always be some average difference between any two groups that are compared on almost any measure of attributes, but that doesn't make the difference 'important', which is a social judgment.

The current study doesn't take us all the way back to Freudian ideas that the first glimpse an infant has of the world is hugely transformative, though who knows what further studies might find. In any case, the important fact is not about the IQ controversy, because there is no reason to doubt that an enriched environment throughout life is an enriching fact of life.

Idunno what it is, but you four always seem to have the best and most apropos posts for what I happen to be teaching at any given time. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteThat's good to hear!

DeleteThanks for this post. I'm struggling with the paragraph starting "secondly" ... if possible, can you please show me the way?

ReplyDeletedoes "from the picture" mean from the world or from an analysis of IQ heritability?

DeleteThis was badly stated, our mistake. Heritability in this context is a ratio of variation attributed to genes, based on data such as correlation of scores among relatives, to total variation. The total variation is modeled as genetic + environmental. If a sample with mixed SES were treated as a single population, but SES is correlated among relatives, that would inflate the apparent heritability--make things seem to be more genetic.

DeleteNormally, if a random source of variation is removed, relatively more of the trait will appear to be genetic. But if family-correlated SES differences were removed, this falsely-attributed genetic variation would be removed, making the actual random environmental effects relatively greater, and hence reducing the heritability estimate.

The issues are subtle, but here a,or the, major point is that very early experiences may make things look more genetic than they really are, if one uses heritability as a gauge of that.

Based on my anecdotal observation, 'intelligence' has very large social contribution and smaller random contribution, which is most likely not inherited.

ReplyDeleteSpeaking of social contribution, I closely track maths olympiad performance. In the year I was there (not from USA), US team was all-white. During those years, the mix was roughly 50-60% Jews and the rest non-Jews. Over the last 6-7 years, almost all members of US team are of Asian origin.

Regarding smaller random contribution - I read the biography of almost all leading mathematicians who lived during the last few centuries, and found a large fraction to be unusually gifted beyond what early training could achieve. There must be something in their brain that worked in the proper way. Among the extreme examples, check about this Indian lady -

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shakuntala_Devi

"Devi traveled the world demonstrating her arithmetic talents, including a tour of Europe in 1950 and a performance in New York City in 1976.[2] In 1988, she traveled to the U.S. to have her abilities studied by Arthur Jensen, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. Jensen tested her performance of several tasks, including the calculation of large numbers. Examples of the problems presented to Devi included calculating the cube root of 61,629,875, and the seventh root of 170,859,375.[3][4] Jensen reported that Devi was able to provide the solution to the aforementioned problems (395 and 15, respectively) before Jensen was able to copy them down in his notebook.[3][4] Jensen published his findings in the academic journal Intelligence in 1990.[3][4]"

Yet I rarely found the kids or parents of gifted mathematician to be equally gifted mathematicians. Sure the sample size is very small, but if there were even a small genetic positive component, the social effect of upbringing (with gifted dad or mom) could helped polish that up to bring up a talented kid.

I've met very few scientists who maintained their rational scientific perspective when it came to matters of race. It's unfortunate, but that's the way it is. Most scientists are particularly sensitive to race/religion/ethnicity issues. It is part and parcel with the whole PhD process. And even for the insensitive ones, who wants to be on the side of the argument that saying that race X is genetically less intelligent than race Y? And who wants to pay to test that?

ReplyDeleteIt's not about science. It hasn't ever been. It's about politics and sociology, and it has no place in science, because it's not proper subject matter, because human limitations make it that way.

Yes.

DeleteThere are serious problems in this world for which research can do social as well as scientific good. There are limited resources, and they're public resources. There is also the repeated lesson of history, the arrogance of power, and all that. Some things don't need to be studied.